Published on: Thursday, 27 September 2018

Last updated: Thursday, 27 September 2018

As the country marks the centennial Armistice Day this November, Claire Wrathall looks at the role East Anglia played in the First World War

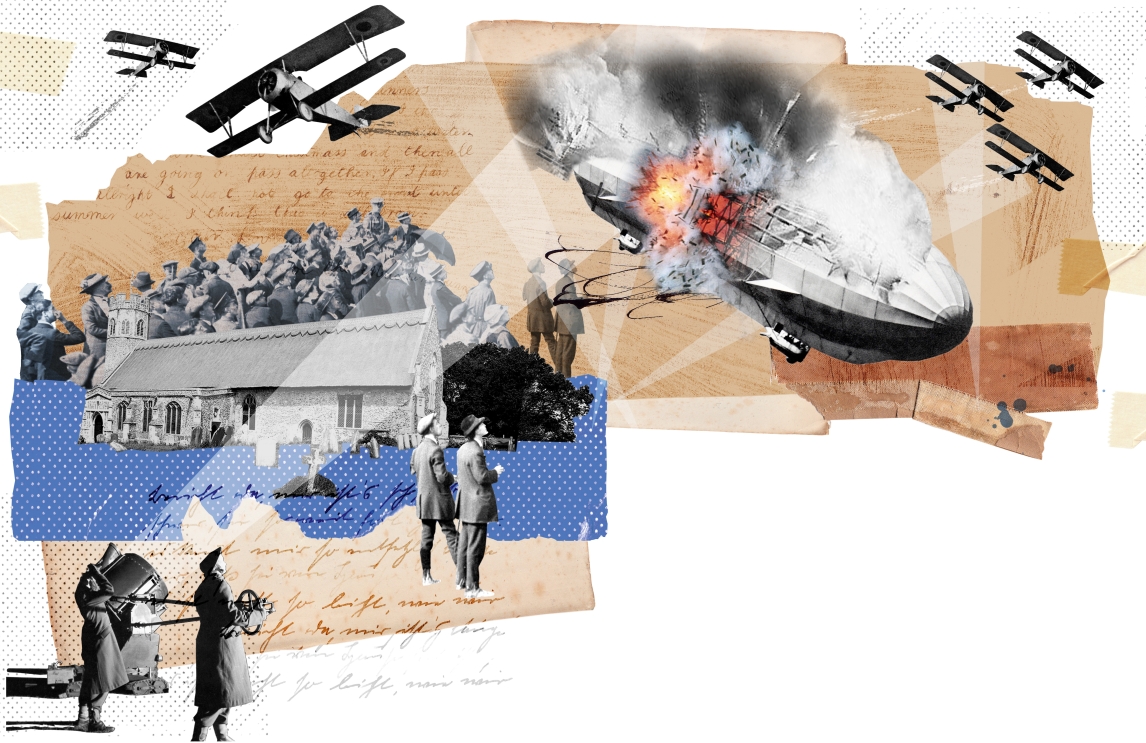

Arrive in the Suffolk village of Theberton, and the sign that stands at the junction of aptly named Pretty Road and Leiston Road is an unusual one. The principal image is of the local Saxon church; and there’s also a windmill. On the right-hand side, however, there is the skeleton of a Zeppelin that crashed nearby in the early hours of 17 June 1917.

L48, as it was named, was a 195m-long hydrogen-filled airship, part of a mission to attack London. The Kaiser no longer forbade attacks on the capital – as he had at the start of the First World War, lest his cousins, the Royal Family, suffer as a result – and had already discharged nine bombs on Falkenham, near Ipswich, 16 on Kirton and three on Martlesham.

By the time she reached Harwich in Essex, however (where, two days after Britain entered the war, HMS Amphion had sunk with the loss of 150 lives when she hit a mine), she was under attack from biplanes from the Royal Flying Corps, which had flown from Orford Ness. Back then this top-secret site was home to the Experimental Flying Section of the War Department’s Central Flying School, which pioneered research into parachute technology, aerial photography and camouflage.

In other words, East Anglia played a truly vital role in the First World War.

The Zeppelin, meanwhile, was losing altitude and drifting in the wind. It was pursued by three fighter planes, which were, incidentally, among the first built by Ipswich engineering company Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies – a specialist in agricultural machinery till the war effort prompted it to diversify into aircraft. In flames, the Zeppelin finally fell to earth on land belonging to Holly Tree Farm, not far from Leiston. Sixteen of the 19 men on board were killed and laid to rest in Theberton churchyard, where their graves remain to this day.

More than 30,000 local people flocked to visit the crash site. But eventually what remained of the airship’s aluminium frame was salvaged, parts of it sawn into 40 souvenirs that were auctioned in Southwold marketplace (there’s still a piece in Southwold church), in aid of the Red Cross, which had set up a military hospital at nearby Henham Hall.

An eminent 18th-century stately home, the house at Henham (now best known as home of Latitude Festival), was demolished in the 1950s. During its years as a hospital its fine rooms were used as wards to which convoys of wounded soldiers were shipped directly from France, and its chatelaine, the Countess of Stradbroke, assumed the role of matron. She was photographed looking saintly and rather nun-like in her uniform for a number of society magazines, not least Tatler.

Even so, Henham paled in scale compared with the First Eastern General Hospital in Cambridge, which was built in a series of prefabricated wooden buildings soon after the outbreak of war on the site of what is now the University library. It had 1,700 beds, not to mention its own post office, cinema and open-air wards so that the wounded could benefit, like the soldiers of Wilfred Owen’s poem Futility, from the warmth of the sun.

So close was East Anglia to Germany and the northern reaches of the Western Front that it played a crucial role in the First World War. Indeed it was said that in certain weather conditions you could hear the roar of guns from the battlefields of Flanders from as far north as Southwold, which suffered its first Zeppelin raids in April 1915 (28 children missed school next morning on account of “the fright” they had suffered), and was shelled by four German destroyers and a submarine in January 1917. With no sirens to warn of impending attacks, the church bells were “jangled”, and tolled when the coast was clear.

Lowestoft also came under attack, too, from four German battle cruisers in April 1916, killing three people and damaging more than 200 homes. The official advice from the County of Suffolk to civilians was to stay in their cellars. Those with homes on the seafront were told to “leave by the back door”. Gathering in crowds “to watch”, it warned, “may lead to unnecessary loss of life”. Not everyone obeyed.

As one Lowestoft man, AJ Turner, wrote of watching the local effort by 19 fishing vessels to quell the attack “from the Hun dreadnought, it was magnificent but not war; it was a case of a wasp stinging a tiger. It was suicide to attack the enemy, but in doing so they drew the fire from the town, and the Huns put their 12-inch guns on them and failed to hit them except once that I saw. The columns of water were going up where the shells went into the sea exactly like very high church steeples all round our boats. I would not have missed seeing it for £50.”

Invasion was a very real threat along the East Coast, hence the lines of concrete and stone pillboxes, fortified round or hexagonal bunkers built in 1916. Thirty-one were built in Norfolk, surviving examples of which can be found at Weybourne, Stiffkey, Bacton, Stalham, Aylmerton, Thorpe Market, Beeston Regis, and Bradfield, near North Walsham.

But East Anglia’s role was not merely defensive. Field Marshal Earl Kitchener, the man with the moustache and the pointing finger on the ‘Your Country Needs You’ posters, was High Steward of Ipswich when the then prime minister, Herbert Asquith, appointed him Secretary of State for War in 1914. His mother had been born at Aspall Hall in Suffolk. Having appended the village name to his title when he was first elevated to the peerage as First Baron Kitchener of Khartoum and Aspall, he continued to spend holidays there and enjoy Aspall cider, the company her family founded, shipping it to India to refresh his troops while he was stationed there.

Not quite 30 miles north-west of Aspall at Thetford in Norfolk, another sort of crucial war work went on at the Elveden Estate. The 7,000-acre farm belonging to Edward Cecil Guinness, Viscount Elveden, of the Irish brewing dynasty, was requisitioned by the War Office and used to test newly invented tanks bound for the Somme and practise tank warfare.

So top secret was the project – one officer described it as “more close-circled than the Sleeping Beauty’s palace, more zealously guarded than the Paradise of a Shah” – that not even its owner knew what was going on, or not until George V was invited to watch a display. Locally, the rumour was that a tunnel was being dug through which Germany would be invaded, hence the repeated explosions.

But ultimately the story of the war as it affected East Anglia is of its people, of those who bravely defended it, military and civilian, and those who died doing so. For example, the St George’s Day raids on German-held Zeebrugge and Ostend in April 1918 – a fiendishly complicated and daring “mission impossible” to block the U-boats that had sunk a third of the Allies’ merchant fleet – was carried out by a substantially volunteer force of 1,600, most of whom were from Norfolk (the Royal Navy Reserve was drawn substantially from those in maritime trades in East Anglia). The mission succeeded, thwarting German attempts to starve Britain into surrendering with a blockade.

Churchill later called it “the finest feat of arms in the Great War”. But there were more than 600 casualties and 227 men died. The names of those who died are inscribed on war memorials and rolls of honour across East Anglia: every town and almost every church or village has one. By this year’s Centennial Armistice Day, more than 150 such memorials across Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire will have been granted Listed status to ensure that we never forget their sacrifice.

Lest we forget

Just some of the centenary events taking place across the network to mark the end of the First World War

Remembrance Sunday/ Armistice Day

11 November

There will be numerous ceremonies across East Anglia at churches, cenotaphs and war memorials. Beacons of Light will be lit at 7pm throughout the UK.

‘Eve of Peace’, Bury St Edmunds

7 November

This evening service in St Edmundsbury Cathedral will include the Standards of Service units, Service charities and local descendants of those who gave their lives.

stedscathedral.org

War Graves Project, Suffolk

8 November

Royal British Legion Suffolk will organise school children to lay poppies simultaneously on the 1,332 war graves in 248 cemeteries across the country, in a moving display.

britishlegion.org.uk

Armistice: Legacy of the Great War in Norfolk, Norwich

20 October–13 January 2019

This major exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery will depict the breadth and depth of the effect of the War on Norwich and Norfolk.

museums.norfolk.gov.uk

Clarion Call, Ipswich

25 October–4 November

This large-scale outdoor sonic artwork will ring out from Ipswich waterfront using audio technology originally employed in war and emergencies.

1418now.org.uk

‘We Will Remember Them’, Norwich

10 November

The Chamber Choir are joined by the Swedish Motet Choir and acclaimed soloists for this special commemorative concert at Norwich Cathedral.

cathedral.org.uk

Journey’s End, Brentwood

8–10 November

Set in a dugout in March 1918, this iconic First World War play by R C Sherriff – performed at Brentwood Theatre – is a deeply moving account of the horrors of trench warfare.

brentwood-theatre.co.uk